An estimated 5.9% of adults in the United States are thought to have ever engaged in self-harm—the act of intentionally hurting oneself via cutting, burning, hitting, or other self-inflicted suffering. Among adolescents, that prevalence is thought to hover around 18%, indicating that more young people are engaging in the act today than in decades prior—an indication supported by research among youth. Such elevated levels of self-harm have been attributed to an apparent increase in mental health issues among youth as well as the contagion effectof self-injurious behaviors, whereby awareness of it as a practice (especially one that is engaged in by a peer) inspires young people to attempt the behavior themselves.

Self-harm is nothing new. Records of the practice date back to Ancient Greece. Some religions have sanctioned it as a culturally justified form of atonement. But while it may have existed for millennia, how people go about it has evolved over time. Today, a new form of self-injurious behavior has cropped up across the United States and abroad: digital self-harm. Though the act itself appears to not involve any immediate physical harm, its associations with additional mechanisms of self-injurious behavior, substance misuse, and suicide risk are alarming.

Digital Self-Harm, Defined

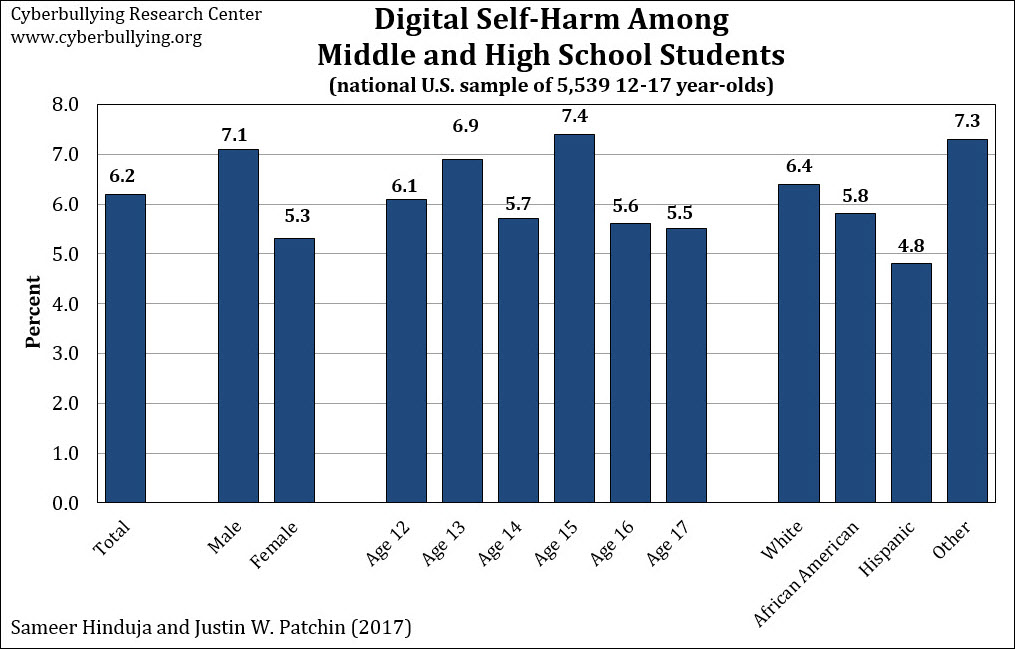

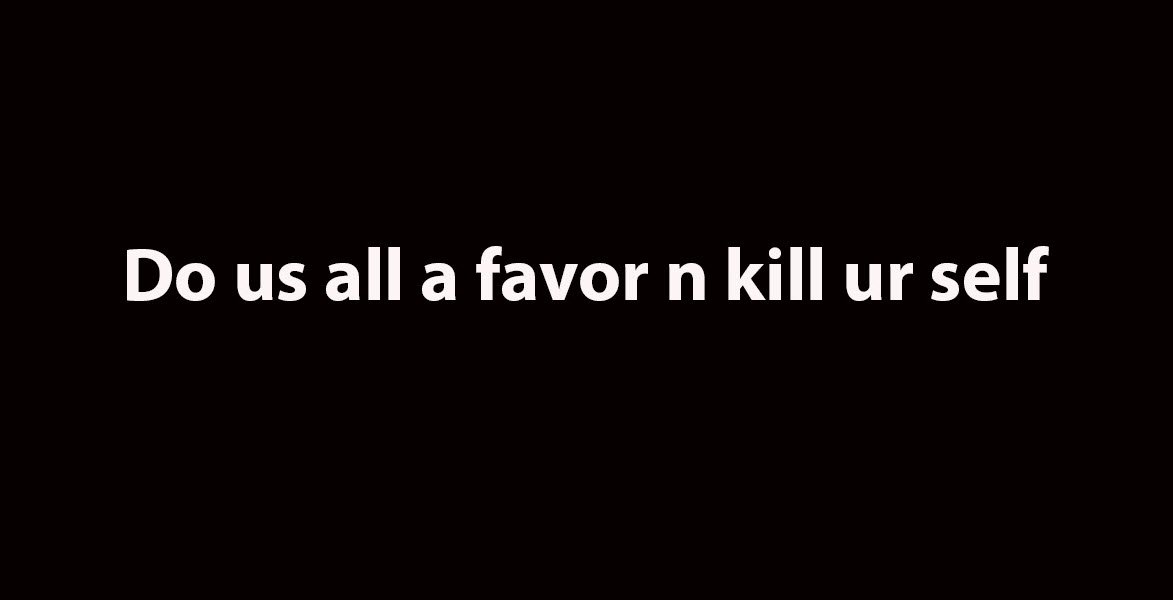

According to criminologist and cyberbullying researchers Justin W. Patchin, Ph.D., and Sameer Hinduja, Ph.D., digital self-harm entails the “anonymous online posting, sending, or otherwise sharing of hurtful content about oneself.” In a 2017 survey of over 5,500 United States youth, Patchin and Hinduja found that 6% of American middle and high school students have ever engaged in digital self-harm, with males being more likely to have done so than females. They project that “about one in twenty 12- to 17-year-olds have participated in the behavior.” Prevalence of digital self-harm among adults is currently unknown.

Adolescents who engage in digital self-harm also appear more likely to engage in offline acts of injurious behaviors directed towards their own bodies (e.g., cutting, burning, head banging). They are at a greater risk of attempting suicide than individuals who do not digitally self-harm. Digital self-harmers are more likely to have been bullied, either online, at school, or in both real and virtual contexts.

Why harm oneself online?

The motivations for engaging in digital self-harm are manifold, and many overlap with the motivations individuals cite when asked why they self-harm “irl.” These motivations include attention and support seeking, emotion regulation, self-punishment, gaining a sense of control, and even boredom. Emotion regulation in particular appears to be a theme across many studies on non-digital self-harm. As Patchin and Hinduja summarize in their 2017 paper, top reasons for physical self-harm reported by thousands of adolescents across America include “the desire to stop bad feelings (such as emptiness, abandonment, guilt, or desperation), to release tension and stress, or because the respondent was unhappy or depressed,” as well as to externalize self-hatred, punish oneself, or combat dissociation (the experience of feeling numb or disconnected from one’s body or identity).

More specific to digital self-harm, Patchin and Hinduja note that “…many who had participated in digital self-harm were looking for a response,” What kind of response exactly? The youth in Patchin and Hinduja’s survey reported several different kinds. These included wanting others’ pity, wanting “to be validated that someone did actually care about me,” and attempting to elicit others’ help (e.g., hoping that another person might come to the assistance of or defend the target of the harmful statement—the individual who made the statement to begin with).

Previous research by psychologist Elizabeth Englander, Ph.D., has found an intriguing gender difference in motivations to engage in digital self-harm. In her 2012 study of digitally self-harming youth, she found that many girls reported digitally self-harming to prove they could handle the aggression while boys reported doing so because they were mad at someone else or wished to provoke a fight.

Patchin and Hinduja note that digital self-harm may be a means of demonstrating one’s toughness, a method to clarify whether negative statements and beliefs about oneself are shared by others, or simply to reify (albeit virtually) the pain and suffering they feel inside.

Digital self-harm may also be a sign of a broader mental illness or personality disorder. Physical self-harmers tend to report higher levels of depression as well as higher levels of anxiety, greater difficulty with emotion regulation, and a reduced capacity to effectively cope in a prosocial manner, so it would make sense that virtual self-harmers would also struggle with these things. Physical self-harm is also common among people who meet the criteria for borderline, schizotypal, dependent, and avoidant personality disorders. Further research may find that individuals who meet these criteria are also more likely to engage in digital self-harm.

How can digital self harm be treated?

Digital self-harm is such a new concept that standardized treatments for it have yet to be developed. Like “traditional” self-harm, however, mental health professionals recommendaddressing the negative underlying beliefs, thoughts, and feelings that give rise to self-injurious behaviors in general in a therapeutic context and guiding youth to find more adaptive ways to achieve the outcomes they seek via digital self-harm.

A first step in finding more adaptive behaviors entails helping someone who engages in self-harm (digital or otherwise) identify the purpose(s) that behavior serves, brainstorming alternative ways to achieve that purpose, and practicing those alternative behaviors. For example, if a youth is digitally self-harming to make their emotional pain known, it would be helpful to identify other mechanisms for communicating negative emotions (e.g., through artistic means or through identifying friends, family members, or professionals that the youth can openly discuss their feelings with). As another example, if the purpose is to regulate one’s emotions, alternative emotion regulation strategies (deep breathing, writing, engaging in vigorous physical activity, taking a cold or hot shower, squeezing ice cubes or throwing ice cubes against a shower wall) can be taught, either by a parent, a teacher, or a mental health professional.

Therapeutic modalities like cognitive behavioral therapy, which emphasizes the challenging of unhelpful beliefs and thoughts as well as behaviors, and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which emphasizes the learning of alternative coping skills and emotion regulation in addition to interpersonal and mindfulness skills, may also be useful in targeting digital self-harm. Psychodynamic therapy, in which someone explores their current emotions, their past experiences, and their interpersonal dynamics (especially between client and therapist—something called transference) has also been shown to ameliorate the severity of (and in many cases extinguish) physical self-harm and may be an additional method of addressing and managing digital self-harm.

More research has to be done to test the efficacy of various interventions, but given the positive outcomes of several different types of mental health interventions upon physical self-harm, the prospect of helping individuals who struggle with digital self-harm appears hopeful.

Source